Elasticsearch at goto conference, making sense of your logs

Make sense of your logs

Britta Weber

Last week, goto conference came back to Berlin. The second edition of this developers conference was better than last year's: More content, a better venue, and great speakers made the two days conference a great place to be. The best thing about goto is how it suits technical and non-technical people working in tech, such as myself, and how many of the talks are relevant for decission makers.

The first talk of the day, after Martin Fowler's keynote, was Britta Weber's 'Make Sense of your Logs: From Zero to Hero in less than an Hour!'.

Britta works at Elasticsearch, the company, and lives in Berlin, so we had met in the Elasticsearch User Group some times in the last months. She knows a lot about how to use Elasticsearch and was always interesting to hear her asnwering questions in our monthly meetup, but she wont beyond this in her talk at goto and focused on resolving the problems many people have when dealing with data.

Using Logstash, Elasticsearch and Kibana 4, Britta made sense of interesting data sets, like the german wikipedia logs, and pleayed detectives to answer the question 'which were the most visited pages on this specific day and why?' in seconds.

As a non-technical person, it was amazing to see how data transforms from a black over while line of non-sense to a beautiful visualisation that makes sense. And the best part of it? It looked easy to do and little code was needed.

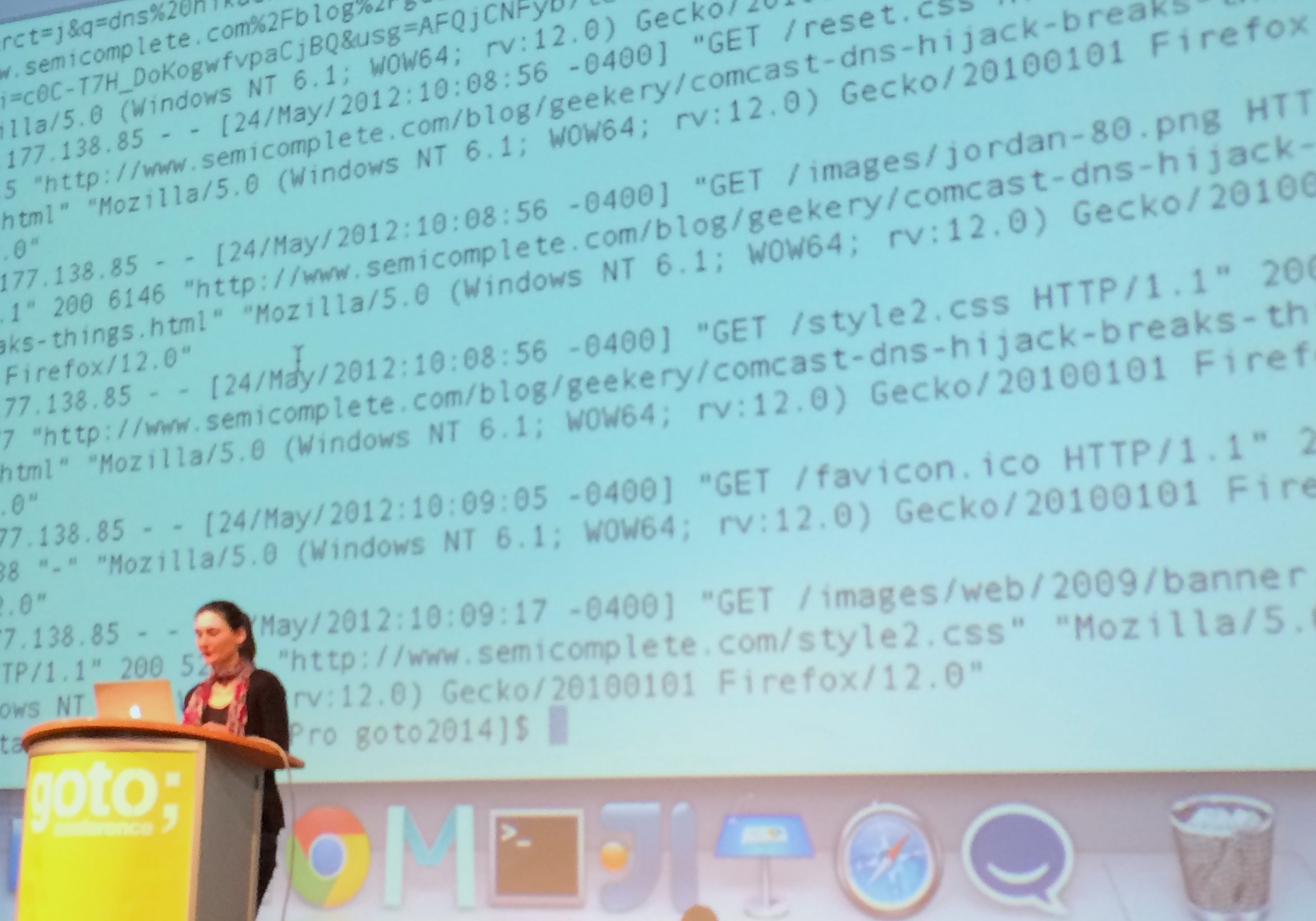

Raw logs, non-sense for most humans

Logs include information about what happens on your computer or application: what information is requested when and by whom, what events happen, what transferences of information are made… They provide valuable information to maintain and fix and improve software, as well as to understand users behaviour. The problem is that different apps write different logs, and they make no sense to most humans - even things like dates, which should be very straightforward, are represented in many different ways in logs.

This leaves the valuable information contained in logs out of reach for people who could actually gain a lot from reading them: business managers, product owners, user experience experts…

Logstash, organised chaos

Logstash already makes it a little bit easier. It takes logs, analyses them to understand their structure, and parses them as blocks that make sense. Britta took the logs above and wrote a very short script to tell Logstash what to do with them. What came out was a cleaner document (indentation! keys and values!) with which it is easy to know what information is contained in logs. Knowing your log files and

Logstash is great to organise your logs and see what kind of information, but does not help a lot with queries. What if you have specific questions about your data, such as when is it used the most or what operative systems do your users prefer? That's Elasticsearch's job.

Elasticsearch, throw all your questions

Elasticsearch let's you make queries about the data you extract from your logs. While logstash told you what was in your documents, it was still hard to make sense of it. Britta showed us how Elasticsearch, used together with Marvel, can make answering these questions and others very easy.

How it works, precisely, is by taking tha data logstash provided and making it searchable. To make this possible, Elasticsearch generates indexes and typer, equivalents to databases and tables, and lets you make queries as you'd do with any other database. Logstash already defaults to one index per day, taking the timestamp from the log and even things like countries or cities were already transformed from the non-sense of the log to readable information simply looking at the IP. This means we can now ask Elasticsearch to return the number of users visiting our site from Berlin, what OS is the most popular, or what file takes the longest to download. Isn't this wonderful?

But the real surprise was yet to come. Being able to query your logs does not fully cover all user cases, and not every person who needs to know this information can query a database. And this is where Kibana 4 comes in.

Kibana, actually making sense

For this demo, Britta put together her favourite pull requests and used a very interesting dataset: two months of logs from the German Wikipedia.

Kibana 4 takes the information Logstash imported and parsed and Elasticsearch stored and made searchable, and puts it together in a graphic interface where virtually anyone can ask the data questions and have them answered in a visual way.

The detectives game started, and the question we wanted to ask our logs was, which were the most visited pages on each specific day? And, more important, why?

Finding out the most visited pages took seconds in Kibana 4. It can be done by selecting a range of dates and selecting 'pages' and 'most visited' as the criteria for the query. Answering why was a bit harder.

When looking at the data, a correlation could be established most of the time between what people searched in Wikipedia and things happening in the world these days, such as revolts and political situations. This was not true for some cases, but could be explained by looking at the Wikipedia Page of the day dataset. If an article was promoted in the Wikipedia home page, visits rose up. It all made sense. Except for one entry: Why were people curious about Jim Morrison, the leader of The Doors, between 10pm and 2am on the 7th December 2013? Jim Morrison did not die on that day, it wasn't his birthday and neither was a tribute album being launched. Then, why? Some google investigation answered the question: a tv show about The Doors was running at that time!

This moment made us all clap. It was impressive how easy it looked to go from chaos to eureka in a few minutes with tools that can be used for free. Reading logs is definitelly not fun for everyone, and making sense of them is probably impossible for most non-technical people, but developers, using the right tools, can move them closer to decission makers and help them answer all the whys they ask themselves and make their jobs easier.